Love for family is a primal force — powerful, endearing and enduring — capable of parting the sea or moving mountains. Imagine if that bond was torn asunder, shattered and shredded in seconds, leaving one not knowing if a family member was among the dead or the living. Imagine if dust were settling on a radically changed landscape, and there was no way to know whether your family had survived or perished.

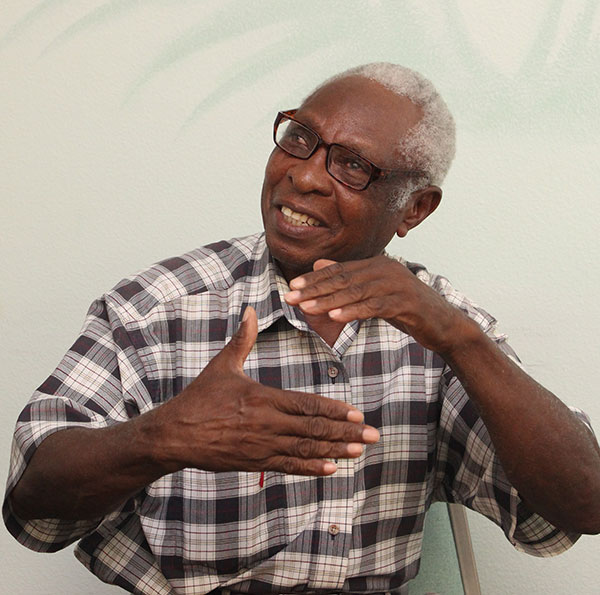

That is the horror 900,000 people faced in January 2010 after a devastating 7.0 magnitude earthquake demolished Port-au-Prince, Haiti. It is the horror that Joseph Jean Pierre, a resident at Cypress Run, a United Church Homes affordable housing community in Immokalee, Florida, faced that day. Joseph happened to be in Haiti, visiting friends and family in Port-au-Prince, when the earthquake struck. In a jarring collision of time and location, Joseph had a front-row view of the most catastrophic natural disaster to ever occur in the Western Hemisphere.

At home in Florida was another Cypress Run resident, Colbert Dolcine, who anxiously watched media coverage unfold in the minutes, hours, days and weeks that followed the disaster. If Joseph’s view was up close and personal, Colbert’s view was from 800 miles away, intimately attached to the fate of his granddaughters, yet also detached in time and space from what was happening.

At home in Florida was another Cypress Run resident, Colbert Dolcine, who anxiously watched media coverage unfold in the minutes, hours, days and weeks that followed the disaster. If Joseph’s view was up close and personal, Colbert’s view was from 800 miles away, intimately attached to the fate of his granddaughters, yet also detached in time and space from what was happening.

For both men, their lives were irrevocably defined into two periods, the before and the after.

Before the quake, Joseph was relaxed, with little to worry about. He was in his homeland and nothing felt more natural. Joseph was enjoying the company of people he loved most dearly, sitting on the front porch with friends and their children. He missed his wife back in Florida, but he knew she would be there when he returned from Haiti.

Then the quake hit.

Many of us have heard people talk about an earth-shattering noise, but Joseph says he literally heard the earth shattering. At one point, he thought the earth would swallow him whole, that God was fulfilling prophecies described in the Book of Revelation.

Many of us have heard people talk about an earth-shattering noise, but Joseph says he literally heard the earth shattering. At one point, he thought the earth would swallow him whole, that God was fulfilling prophecies described in the Book of Revelation.

The quake threw Joseph from his chair. A child who moments before had been playing in the yard landed on top of him. Screams filled the air. Dust choked out the sun. Buildings around him collapsed, with one level pancaking atop another, crushing everyone inside. Joseph began to pray.

Miraculously, his friends’ home remained standing. They had survived. They were blessed. The earth finally settled, its angry cry silent for now. Those who were able began to clear debris. A truck moved through the neighborhood, and emergency workers pitched dead bodies, like garbage, onto the vehicle.

This was Joseph’s “after.” Nothing would ever be the same. Before, he might have worried he had misplaced his glasses, or whether he would make it to church before the morning prayers started. After, he was afraid to go inside, fearing the structure could still collapse, anxious about every aftershock, uncertain about facing more destruction and death. Joseph remained on the sidewalk, praying, for three days.

Back in Florida, his wife and children grew increasingly concerned after being unable to reach Joseph and waiting for days with no word about his status. They began to mourn the probable loss of their beloved husband and father. Just imagine their shock when they learned that Joseph was alive and uninjured. They were reunited a few days later. The family gave praise that he had survived unscathed.

It was in the “after” that Joseph found peace. Back home with his wife and children, he knew he had come ever so close to never seeing them again.

Joseph and his family were fortunate. Many others were not. More than 200,000 people died in the quake and in the weeks that followed. More than 1.5 million Haitians lost their homes. Whole towns and sections of cities were erased. Overnight tent cities were erected on the rubble. Haitians had no food, no water and no safe place to go.