The command was neither invitational nor gentle. Nor did it involve a courtroom and a swearing in. Maybe a little swearing at!

It was about being male freshmen concert choir members on tour. Platform risers had to be unloaded from the tour buses as soon as the group arrived at the day’s church or auditorium. Once inside, the rises had to be quickly placed where and in whatever arrangement the “upper” class men demanded. Rehearsals for the evening’s concert were expected to begin within minutes of arriving at the concert venue!

It usually took two freshmen “grips” to carry one riser. “Take the stand” meant one of them was expected to carry a riser and the choir director’s music stand.

There were no other stands – only that one. Except for the year the choir presented the Listz-Reibold little known choral version of “Preludes to Eternity.” The small orchestra needed for accompanying the choir had to carry their own folding music stands. But any freshmen instrumentalists still had to carry risers first, and one of them had to take the director’s stand.

So “take the stand” meant engaging first in setting the stage for the good of the choir and the pleasure of the audience, before tending to one’s own needs.

Perhaps it is a metaphor for today. In a time when our nation feels eviscerated by raucous contradictory claims, and severely divided by state and federal rulings, we need to reconsider what tending to the good for the other – for all others – would look like in such times.

Award winning columnist Leonard Pitts, Jr. observed that national polling indicated a progressive majority opinion was registered on virtually every social issue. He then opined, “But having the majority means nothing if you lack the will or the wit to wield it.”

At some point in my music-stand carrying days I heard the famous American bass-baritone Paul Robeson sing. Persons in my generation know him best for his richly resonate singing of the Jerome Kerns-Oscar Hammerstein “Old Man River” from their musical SHOWBOAT.

Less known is that Robeson attended Rutgers, and even though a southern football team refused to play the Scarlet Knights because Rutgers fielded a black man, he was twice named an All-American football player, graduated as valedictorian, earned a degree from Columbia Law School while playing in the NFL, and established himself as a global concert artist and political activist.

We might agree that he exercised the “will and wit” which columnist Leonard Pitts declared is necessary to exert influence.

Long before we knew about Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, Robeson’s advocacy and controversial social views led to his being banned from making public appearances. When he was denied a passport for overseas travel by a McCarthyist FBI and later appealed the reasoning, he was told “his frequent criticism of the treatment of blacks in the United States should not be aired in foreign countries.”

Here was an African-American man with extraordinary gifts and opportunities, denied lodging in hotels during his concert tours, regardless of his fame and talent. Those of us who fastened only on his glorious singing voice, missed subtle phrases in ‘Ol Man River’ like “those who plant cotton are soon forgotten …” and “show a little grit and you lands in jail.”

When asked why he was determined to stand for better regard for persons of color, Robeson replied, “My father was a slave and my people died to build the United States…. The question is whether American citizens, regardless of political beliefs and sympathies, may enjoy their constitutional rights.”

It is still apparent in the culture around us these days that we too often disregard the contribution of the African slave to the wealth of white America, and the disproportionate incarceration and killings of African-American men.

Paul Robeson is but one story of individuals who, against all odds and in the face of sometimes brutal treatment and disregard, stood up, stood out, and stood for “a better legacy for the future, even knowing (he) may not personally benefit from a brave new world.” (Paraphrased from a remark by Leonard Pitts, Jr.)

At one point, the New York Times wrote this:

“This amazing man, the great intellect, this magnificent genius with his overwhelming love of humanity, is a devasting challenge to a society built on hypocrisy, greed and profit seeking at the expense of common humanity.”

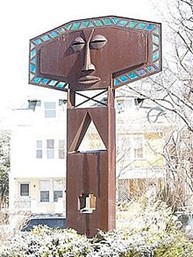

It took many years after his death in 1976 before parks, boulevards, lecture halls, buildings, and statuary were crafted to acknowledge and capture the memories of a much maligned and punished stalwart whose memoir is in fact titled “Here I Stand.”

There are, of course, countless other persons of courage and determination, who use their skills and position to influence public attitudes and political decision-making.

Today, standing tall with less regard to our own age, circumstances, welfare, or popularity, may be the greatest gift we can make for the preservation of a civil, humane, just, and peace-filled society.

Perhaps those of us who once cowered to the “upper” classmen who made us carry the risers and the director’s music, need to strap on our Paul Robeson’s and “stand on the holy ground of neighbor love.” (Quoted again from Leonard Pitts)

Prayerful kneeling to seek strength and courage to love our neighbors – all neighbors – may be the first step to “Take that stand!”

View all articles by: